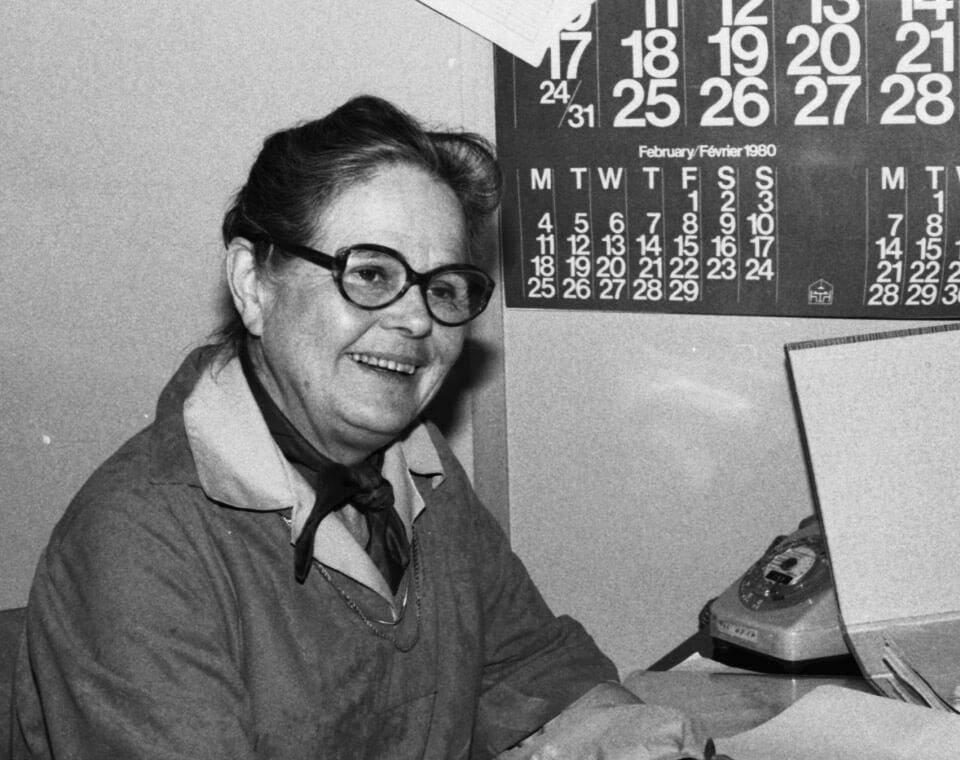

Profile of Edith Penrose (1914-1996)

- ECOINT

- Feb 9, 2024

- 4 min read

Updated: Feb 10, 2024

By Glenda Sluga | 2023

From the 1950s to 1970s, Penrose published the following major texts:

The Economics of the International Patent System, Johns Hopkins Press, 1951

The Theory of the Growth of the Firm, John Wiley and Sons, 1959

'The Growth of the Firm—A Case Study: The Hercules Powder Company', Business History Review, 34(Spring Issue): 1-23, 1960.

The Large International Firm in Developing Countries: The International Petroleum Industry, Allen & Unwin, 1968

New Orientations: Essays in International Relations, with Peter Lyon, Frank Cass & Co, 1970

Iraq: International Relations and National Development, with Eranest Penrose, Westview Press, 1978

Why is Edith Penrose an international economic thinker?

Edith Penrose (née Tilton) was a 20th century political economist whose analyses of business, work on the multinational firm, and particularly oil industry has captured the interest of some business and management historians. She is regarded within business history as an ‘industrial economist’ already known for her work on the firm, ‘concerned with the motivations, conduct and performance of firms, market structures, growth and profits, competition and bargaining.’ More recently, she has been characterized by new feminist work on international political economy as a thinker who contributed to ‘[i]nternational economic development, emerging out of colonial economic administration’.[i]

We can consider Edith Penrose an international economic thinker because, firstly, she was substantially involved in the work of international economic organizations through much of the 20th century; secondly, she introduced new ways of thinking about, and taking seriously, the political and financial operation in the Global South of vertically integrated-multinational firms with headquarters in the Global North. The oil industry, and the tiers monde (her preferred term) more generally, were incorporated into thinking about how economies work in an international economic landscape. Her training and her experience drew together many strands of international economic thought: from the social justice strains of the ILO, and ‘tiers monde’ consciousness of UNCTAD, to the trade and monopoly concerns of the (so-called) ‘Austrian school’, thanks to the influence of her thesis supervisor Fritz Machlup. She has been characterized as concerned with ‘monopoly, innovation and social welfare.’[ii]

Like other scientific thinkers of her generation, Edith Penrose understood inequality to be the source of instability. Her work experience also led her to see economic inequality in international economic arrangements, as much as within national settings. She was American born and educated, employed in Geneva- and then New York, first at the ILO, and then at the UN. A graduate of UCLA Berkeley economics (1936), her first position was at the ILO as an assistant to its economic adviser, Ernest Penrose, her former professor (and, later, second husband). Penrose was adviser to the American John Gilbert Winant, third director of the ILO (1939-1941). In her capacity as his junior assistant, Edith worked on the effect of war displacement in the world textile industry, and infant mortality, and helped with research for Studies in War Economics (1941). When, during the Second World War, the ILO moved to Montreal, Edith moved too. During this period at the ILO--an institution that was constitutionally focused on social justice achieved through the improvement of the standard of living-- Penrose decided she wanted to become an economist. Her ILO research examined wartime food production and distribution in Britain, with particular attention to the role of the government in this domain; she termed British policy a form of ‘applied socialism.’. Food Control in Great Britain was eventually published by ILO under her name Edith Derhardt. She was not inclined to romantic or idealist economic views, but she was attuned to the question of what economics was for, much as posed by Bruce report and its authors in this same period. During the last years of the war, she became involved in the ‘Inter-Allied Postwar Requirements Bureau’ in Washington D.C. Her task, again alongside Ernest, was ‘to do the economic thinking’.[iii] In that role, Edith participated in numerous intergovernmental meetings that set the postwar international agenda, and she expanded her economic networks.

Penrose’ international career in many ways tracks that of other women employed at the ILO, and many more who moved in and out of international institutions in the post-second world war, contracted as consultants writing research papers and studies, rather than as full-time staff. Added to this, her academic career spanned newly established Middle Eastern and British economics departments. Over a period of nearly two decades, Edith developed the field institutionally and more broadly, and co-founded the Journal of Development Studies. At that time, economic journals did not publish on questions of economic development. For Edith Penrose, the point was to not only cultivate expertise regarding the economies of developing countries, but to also link knowledge about their political development to their economic development, and vice-versa.

In the course of her academic career, Edith Penrose continued to work as an international consultant. Edith advised UNCTAD, and attended the 1972 UNCTAD conference in Santiago, where she participated in the rethinking of the relationship of ‘development’ as a ‘northern’ concept to ‘Third World’ demands for equality through trade and financing. Penrose not only saw the world as a place bigger than any one nation, she also acknowledged theilliberal conditions of the international economic order, skewed in favour of the so-called ‘first world’. Sheintroduced these themes to economic thinking as a way of qualifying the claims and expectations surrounding economic integration. Later in her life, Penrose would critique a World Development Report for urging ‘Integration into the world economy . . . apparently in all innocence,’ ‘in the name of “liberalization”, in spite of the fact that the international economy is not particularly “liberal”. The Bretton Woods institutions and the developed industrial economies that supported them based their arguments for openness to the world economy on the fundamental assumption that the appropriate international division of labour and the realization of a country’s comparative advantage are best achieved by free market forces.’[iv]

[i] The biographical detail in this study is taken from a range of sources, particularly Angela Penrose, No Ordinary Woman: The Life of Edith Penrose (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018); see also Owens, Rietzler, Hutchings and Dunstan, Women in International Thought: Towards a New Canon? (Oxord University Press, 2022).

[ii] Christos N. Pitelis. “Globalization, Development, and History in the Work of Edith Penrose.” The Business History Review, vol. 85, no. 1, 2011, pp. 65–84. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/41301370. Accessed 24 Dec. 2022.

[iii] Cited in Penrose, No Ordinary Woman.

[iv] Ibid.

Reference anything from this site as:

Sluga, Glenda (2023) 'International Economic Thinkers-Profile: Edith Penrose', ECOINT IET Profile #1, available at: https://www.ecoint.org/post/profile-of-international-economic-thinkers-penrose